Mary Wollstonecraft and other denizens of Somers Town

Way back in the 1960s, in my first weeks as a student at University College, London, I wandered the neighbourhood of Gower Street after classes, absorbing the atmosphere of its grand Georgian squares and the network of small streets between. Soon my walks took me beyond respectable Bloomsbury and the somewhat more louche ambiance of Fitzrovia, south to Soho and Covent Garden (not yet the up-market tourist area it’s since become). But I never crossed the Euston Road, because the area immediately to the north between the great railway stations of Euston, St Pancras and Kings Cross looked run-down and uninviting.

It wasn’t until I read Claire Tomalin’s groundbreaking biography The Life and Death of Mary Wollstonecraft, which reintroduced the 18th century feminist to a new generation, that I first made my way to the district known as Somers Town where Wollstonecraft had briefly lived until her death in 1797.

An exceptional woman by any standards and certainly those of late 18th century England, Wollstonecraft worked as a reviewer, translator and author. At the age of thirty-three, having gained a certain notoriety with A Vindication of the Rights of Man followed by her better-known Vindication of the Rights of Woman, she set off alone for Paris in 1792 to witness the French Revolution. While there she entered into a relationship with an American, Gilbert Imlay, and became pregnant. When Imlay left her for an actress not long after the birth of their daughter, Fanny, Wollstonecraft suffered great mental distress, but nonetheless continued to write and publish, in particular a book on her Scandinavian travels in 1796. Back in London, she began a relationship with the political philosopher William Godwin (author of an Enquiry Concerning Political Justice and its Influence on Morals and Happiness). When she became pregnant again, they married in March 1797 and set up house in Somers Town. At the end of August, Wollstonecraft gave birth to a second daughter (the future Mary Shelley), only to die of septicemia eleven days later. She was buried in nearby old St Pancras churchyard where her tomb can still be seen, though her remains along with Godwin’s were moved to Bournemouth by their grandson Percy Shelley when excavation for the railway threatened the old churchyard.

An 1815 view of old St Pancras church where Wollstonecraft was married in March and buried in September 1797. The river Fleet has long since been covered over.

Throughout the 18th century a favourite destination of Londoners on fine Sundays was St Pancras Wells, the site of a mineral spring “highly recommended by the most eminent physicians in the kingdom”, according to its proprietor. He also offered a variety of refreshments that included syllabubs made from the cream of his own cows. But these “genteel and rural” gardens, laid out in treed walks, were soon to be encroached upon by the growing city.

When Wollstonecraft and Godwin moved to the new development of Somers Town (named for Lord Somers from whom the land was leased), it was still situated among market gardens and meadows where Wollstonecraft’s little daughter, Fanny Imlay, now almost three, joined the hay-makers with her toy rake. They moved into the brand-new Polygon — a circle of thirty-two linked houses built around an inner garden in the centre of Clarendon Square, designed by a French architect, Jacob Leroux, who himself resided nearby.

From a later 1850 sketch. The Polygon is on the left.

Unfortunately, with the monetary crisis caused by the outbreak of war with Revolutionary France, Leroux had difficulty marketing the houses. They were sold at a loss and let at low rents, which is no doubt why a couple like Godwin and Wollstonecraft, making a modest income by their pens, could afford to live there.

Many of Somers Town’s first inhabitants were impoverished French émigrés who had fled the Revolution and taken refuge in London. A Roman Catholic chapel had opened nearby to minister to their spiritual needs (replaced in 1808 by the church of St Aloysius, visible in the picture above), and for convivial society there was a coffee house, which has given its name to a 1920s pub on Chalton Street, the ‘Somers Town Coffee House’.

My novel, A Promise on the Horizon, imagines one such émigré family and their young daughter, Marie-Honorine de Vernet, who meets Mary Wollstonecraft — Mrs Godwin as she calls her — in the months before Wollstonecraft’s tragic death and will be inspired by Wollstonecraft’s travel writing to set out on her own journey.

Some of the French émigrés (like Marie-Honorine’s mother) died in exile and were buried in the churchyard of old St Pancras, which had traditionally been the last resting-place in London for Roman Catholics during the post-Reformation period when there were no Catholic churches in Britain. Among the exiles who never returned to France was the Archbishop of Narbonne, whose remains (including an expensive porcelain denture) were recently unearthed in excavations for the new Eurostar railway at St Pancras International. See http://historybound.co.uk/the-archbishops-teeth/

Before long, what had been intended as a middle-class suburb enjoying fresh country air and views of the Hampstead hills was taken over by small builders who put up humbler housing. The hay-fields where little Fanny Imlay had played were soon occupied by brick-kilns and vast dust-heaps where refuse-collectors dumped the ashes from the city’s fireplaces along with other waste. Wellcome Collection. CC BY

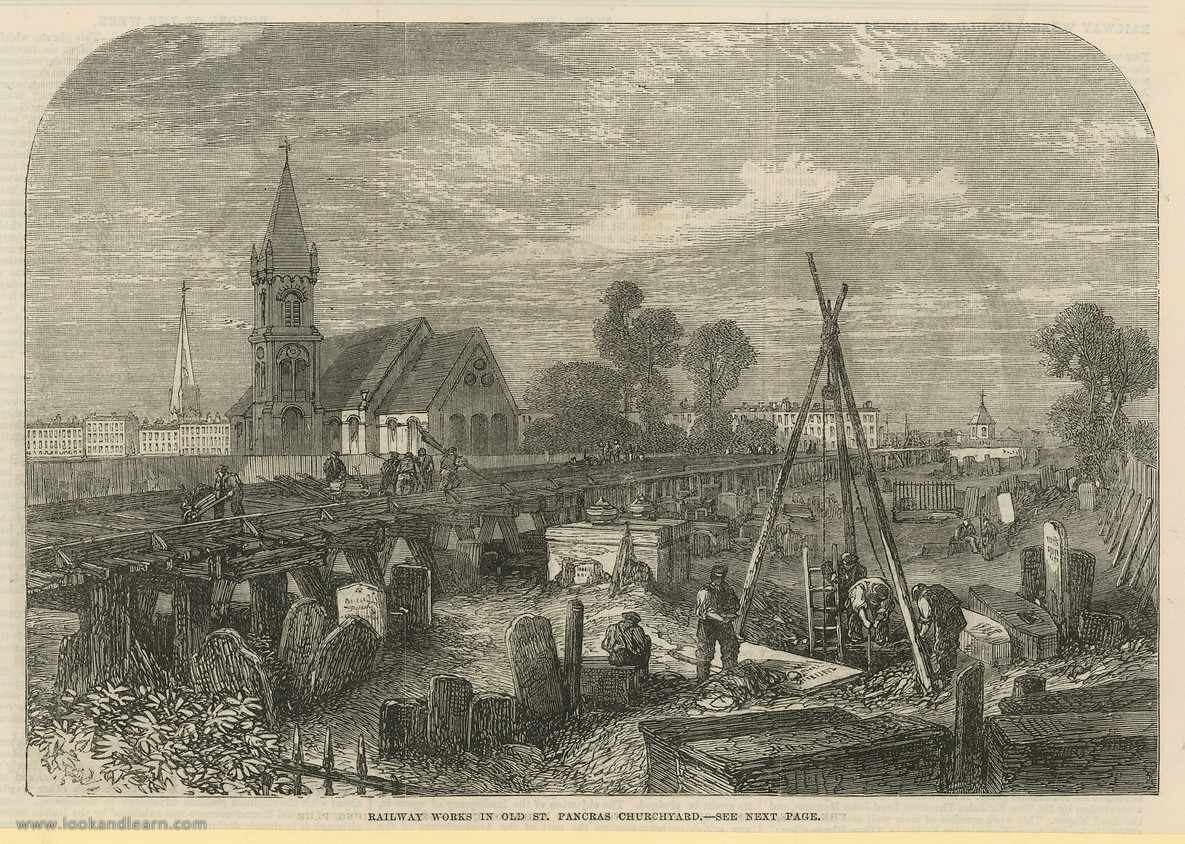

And then, starting in the late 1830s, came the railways, cutting great trenches through the neighbourhood, displacing large numbers of poor residents and not respecting even the dead, who were unceremoniously dug up and reburied in a common pit. A picture in the Illustrated London News of August 11 1866 shows the scene, which caused public indignation.

All this construction brought an itinerant population of labourers, who crowded into the remaining houses, often entire families to a room. The appalling conditions were notorious until early 20th century campaigns for decent housing started to transform the neighbourhood for the better.

On my first visit to Somers Town I’d naively hoped to find some traces of the 1790s. But Jacob Leroux’s elegant Polygon had long vanished, demolished a century later and replaced by Polygon Buildings, a grim barracks-like block for those made homeless by the building of St Pancras railway station. It in turn had been demolished and replaced by Oakshott Court, a more humane development of staggered low-rise apartments designed by a Hungarian architect, Peter Tábori, another émigré whose family fled after the Soviet Union crushed the 1956 Hungarian Revolution.

On an outer wall of Oakshott Court I found a plaque commemorating Wollstonecraft’s residence at the Polygon.

https://www.londonremembers.com/memorials/mary-wollstonecraft-nw1

Delighted as I was to find it, I was surprised that there was nothing for William Godwin or Mary Shelley, though they had lived on at the Polygon for another eight years after Wollstonecraft’s death. Godwin, an influential political philosopher, and Mary Shelley, future novelist and author of Frankenstein, surely deserve their own plaques on the site. Dickens, too, had briefly lived in the Polygon and mentions it in several of his novels, but he doesn’t lack for plaques elsewhere in London.

But what I did find, which was even better, was an astonishing mural that crammed nearly two hundred years of local history onto the side of a building nearby.

Photograph from 1984, kindly supplied by the artist, Karen Gregory. Note the cars on the street to the left and the empty ground in front (possibly a second world war bomb-site), which local children, portrayed in the foreground of the mural, are planting.

The mural reads from right to left. The right-hand side depicts the past with hay-makers and a hay-wain (after the well-known paintings of George Stubbs and John Constable) and the old church of St Pancras (before its Victorian remodelling) above the river Fleet. On the left-hand side in the background are the Somers Town dust-heaps and the brick kilns that announce the gradual encroachment on the fields. The shiny black steam locomotive crossing the bridge marks the arrival of the railways, and on the skyline rise the tall factory chimneys of the 19th century, bringing with them a new population of labourers and their families, a trickle swelling into a crowd.

What’s most astonishing about the mural, given its size and complexity, is that Karen Gregory has twice repainted it on different sites. The first version (the one reproduced above, which I saw in the 1980s) was painted on the east wall of St Mary & St Pancras primary school and took Gregory three years. But in 1996 the waste ground alongside was purchased for housing, so having fundraised with the help of Claire Tomalin (author of the Wollstonecraft biography mentioned earlier), Gregory bravely set about repainting it on the other end of the building. A mere decade later, when the old Victorian school was demolished, Gregory recreated the mural yet again on a wall which now forms a backdrop to the new school’s playground. Unfortunately, though it provides the children with a vivid illustration of local history, it’s now difficult for outsiders to enjoy since the playground is surrounded by a high wire-mesh fence, so the mural can only be viewed from outside and sideways-on, which makes it impossible to photograph.

What pleased me most when I first came across the mural was the image of Mary Wollstonecraft and and William Godwin seated beneath a tree on the bank of the river Fleet. At their feet, little Fanny Imlay is launching a paper boat. Upstream, on a rustic bridge behind the washerwomen, stands Fanny’s half-sister, Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, and her future husband, the poet Shelley. The pale face of Frankenstein’s ‘Monster’ (as incarnated by Boris Karloff) emerges from the bushes behind them.

Right-hand side of first version

Right-hand side of third version [photograph supplied by Karen Gregory]. The colour and many of the figures differ from the original.

Right-hand side of third version [photograph supplied by Karen Gregory]. The colour and many of the figures differ from the original.

The idyllic pastoral scene, so beautifully depicted above, is only one aspect of the 18th century, however. Evoking its darker aspects, Gregory has placed prominently in the left-hand foreground the tragic figure of a young chimney-sweep, familiar to many of us from the poems of Wollstonecraft’s contemporary, William Blake.

The top-hatted man whose hands are on the boy’s shoulder is his cruel master, though the top hat initially made me wonder if he was one of the many campaigners like Lord Shaftesbury who tried for decades to get the practice of sending boys up chimneys banned by law. The bearded man to the right in the close-up is another social campaigner, Charles Dickens, some of whose fictional characters also appear in the crowded scene.

It would be wonderful to have a complete key to all the different groups and individuals who feature in the mural. Many of them are local heroes who campaigned for decent living conditions or worked to advance the position of women. It was the feminist film-maker and social activist Sue Crockford (head of the Somers Town Youth Centre for many years) who suggested to Karen that she portray some of the notable women associated with the neighbourhood. One of the most remarkable is Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (1836-1917), the first woman doctor in Britain, who founded the nearby St Mary’s dispensary for the poor, which eventually became the New Hospital for Women where women doctors could train and women patients could receive treatment from one of their own sex. The hospital frames the left-hand side of the mural. It took nearly three quarters of a century to fulfill Mary Wollstonecraft’s bold assertion that women “might certainly study the art of healing and be physicians as well as nurses”, but she would have rejoiced to see her faith in women’s capacities realised at last.

In the unrelenting process of growth and modernisation, every large city has seen whole neighbourhoods altered beyond recognition, but Somers Town has undergone more change than most. Transformed in the two centuries since Mary Wollstonecraft lived there from rural landscape to urban slum, sectioned by the railways, shattered by bombs in the second World War, bulldozed more recently for grand institutions like the British Library or the Francis Crick Institute, it has persisted through constant demolition and rebuilding. It still has its émigrés, but now they come from all corners of the world like the Hungarian architect of Oakshott Court, or the children at play together this year when I revisited Karen Gregory’s mural. In this neighbourhood which has so frequently felt the wreckers’ ball, it is perhaps the many schools that testify most visibly to the continuing existence of a community. Their very presence suggests that a measure of stability has finally been achieved and it is altogether fitting that in all three versions of the mural, Karen Gregory has placed the schoolchildren at the centre.

Many thanks to Karen Gregory for supplying the photographs of the mural.

For a full account of the mural’s history and an interview with Karen, see:

https://www.forwallswithtongues.org.uk/projects/history-of-somers-town-1984-karen-gregory/

For a key to some of the historical figures represented, with brief biographies, see: https://www.londonremembers.com/memorials/somers-town-mural

Another very interesting post on Somers Town which also features the mural is at https://gerryco23.wordpress.com › 2012/10/25 › the-mean-streets-of-some…